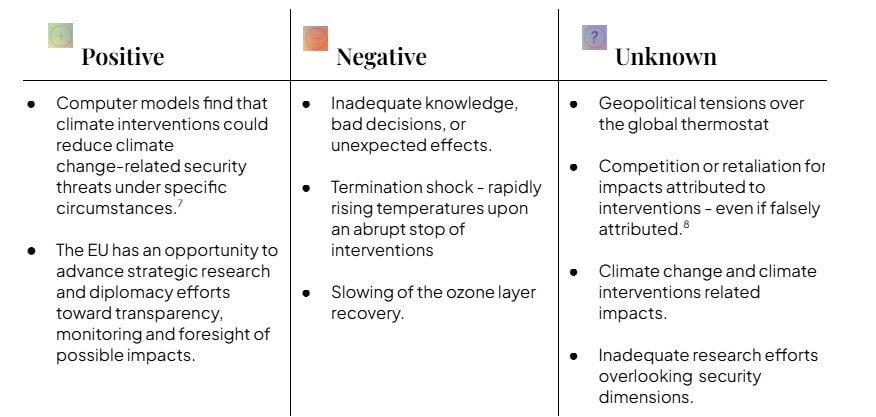

Insufficient knowledge of security-relevant climate interventions risks and climate interventions benefits is an obstacle to responsible and informed decisions. Should such evaluations become necessary, they would need to rely on responsible research having examined security dimensions across future scenarios of climate change with and without climate interventions.

Key security implications of climate change and climate interventions

Human security

- Food: Weather extremes can disrupt crop yields and undermine food security. Reasonable deployment of climate interventions lowers disruption risk, but residual changes and variations in weather patterns across regions may persist.

- Water: Climate change destabilizes the global water cycle, exacerbates drought and flood risks and alters regional precipitation patterns.[9] Careful climate interventions may limit the change but regional changes may still happen, including the South Asian monsoon serving over a billion people.

- Health: Climate change causes health stress and increases mortality including through heatwaves and disease. Climate interventions are the only way to quickly reduce heat, but disease vectors may still be altered.

- Economic security: climate change threatens progress on economic development, including in vulnerable regions and puts sustainable development progress at risk.[10] Responsible climate interventions could theoretically improve economic indicators in most regions, but there are large uncertainties.

Earth and ecosystem stability

- Biodiversity: Climate change is increasing biodiversity loss and shifting animal migration patterns, undermining human livelihoods. Climate interventions could limit changes, but unequally, and introduce some additional changes (e.g. due to a higher ratio of scattered light).

- Security and Earth systems stability: Climate change increases the risk of catastrophic, irreversible shifts in key systems, such as the Arctic or the Atlantic Ocean currents that warm Europe (AMOC). Climate interventions deployed early might reduce risks, but deployed too late would add a layer of complexity. In all cases, it would come with uncertainties and governance challenges.

Political security

- Migration: Disruptions of livelihoods and living conditions are contributing to the movement of populations, which is expected to rise dramatically in the coming decades. Climate interventions could reduce migratory pressures in some regions, but might not address those in other regions.

- Technological competition: World powers are racing to dominate new technologies with profound global impacts. Humanity has only one shared atmosphere, which needs to be managed cooperatively rather than through competition.

- Contested governance: There is a risk that some powers gain early, outsize control over the governance and use of climate interventions. Disagreements on timing, form and inclusivity of (non-)deployment decisions appear likely. Climate interventions will require stable, continuous global governance over many decades to avoid termination shock (see below).

- Winners and losers: While well-designed deployment of some climate interventions could benefit some of the global population and attenuate climate change’s threat of inequality, hasty implementation or unexpected effects could also lead to outcomes in which inequality is exacerbated with climate interventions.

- Risk of conflict due to demands for compensation: Any residual climate impacts – whether attributable to climate interventions or not – could trigger demands for compensation or even lead to conflict.

- Geopolitical conflict: Climate change is currently exacerbating the causes of many conflicts. Successful climate interventions could reduce some of these, but introduce new risks, including disagreements over causality, governance and responsibility for trans-national impacts.

- Political polarisation: Many societies are already divided over policy questions on how to tackle climate change. The prospect of climate interventions is likely to be highly contested, and prone to rampant mis/ disinformation, conspiracy theories and accusations

- Abrupt popular demand for climate interventions: Lethal heat waves, among other climate impacts, could rapidly lead to societal unrest, rapid migration flows, and demands for immediate action. Climate interventions could potentially ease pressure on this issue, but trigger others.

- Entrenchment of conflicts over beliefs and values: Many communities have fundamental moral, religious, and ethical objections to engineering the climate.

- Communities or countries with different positions could trigger or increase tensions. Science is unlikely to resolve those tensions.

Climate interventions research and uncertainty

- Scientific uncertainty and insecurity: Risks from a lack in monitoring capability, climate impact attribution, are currently very high due to the absence of coherent public research programs.10

- Risk of misinformation: The absence of a healthy research ecosystem across technical and social science domains and effective science-communication efforts accentuates the public information gap and fuels misinformation risks.

- Lack of policy-facing scientific synthesis: The lack of comprehensive international science coordination exacerbates insecurity associated with risks of badly informed policy choices.

- Lack of trusted international assessments: The lack of assessments by a trusted international body such as the IPCC or UNEP undermines trust for international cooperation due to vast information deficits among many governments especially in the global south.

Climate interventions deployment specific implications

- Termination shock: Were certain climate interventions to be suddenly stopped, they could lead to a rapid rise in temperatures to previous levels and cause massive harm to people and ecosystems. Effective governance and safeguards could reduce that risk, but would need to be in place over decades, if not a century or more.

- Weaponization or diplomatic threat: Climate interventions are an easily detected, blunt instrument that is unlikely to be suitable as a targeted weapon. The threat of deploying climate interventions – or doing so in a particular manner – may provide first or dominant movers with geopolitical and security advantages.

- Counter-geoengineering: If countries disagree over deployment, there is a risk that some may threaten – or take – measures to counter climate interventions. Experts indicate this would not be effective, but the mere threat may be problematic enough.

Insecurity from poor governance

The IPCC, UNEP and several security-focussed organisations (see annex) describe the lack of governance of climate interventions as a risk in itself. Effective, anticipatory governance could minimise the chances of hasty, rogue or ill-considered activities.

- The security risks rise with delays in developing regional and global governance.

- Short-sighted governance that fails to ensure responsible research, trust-building, transparent monitoring, and international cooperation can, however, exacerbate security threats.

- Multilateral governance can take years to develop, requiring action now.

Our take:

Based on the above, we recommend the EU develop a comprehensive Climate Security Strategy, outlining response options for major disruptions such as a halt of Atlantic meridional circulation, atmospheric destabilisation from polar ice melt, or unilateral climate interventions with regional or global impacts.

This strategy should utilise the foresight capabilities of the European Union Institute for Security Studies ( EUISS) and the European External Action Service (EEAS), along with the expertise of the European Space Agency (ESA), the European Research Council (ERC), the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission, and the European Defence Agency (EDA), and leverage European research through Horizon Europe to reflect the full risk-management landscape for climate and potential interventions.

It should inform defence, infrastructure, adaptation, trade, and migration policies, enhancing the EU’s strategic capabilities to anticipate and respond to developments that can arise within years.

Authors

Matthias Honegger Program director – Climate Interventions

Cynthia Scharf Senior Fellow – Climate Interventions

Giulia Neri Senior Policy Advisor – Climate Interventions

Roxane Cordier Researcher – Climate Interventions