The EU AI Act: Regulatory Exemplar or Cautionary Tale?

Daan Juijn & Maria Koomen | June, 2024

On May 21st, 2024, after three years of painstaking negotiations, the Council of the European Union approved the final version of the European Union’s AI Act. Some call it a landmark regulation solidifying the EU’s leading position in responsible tech governance. Others see it as a death knell for Europe’s tech sector. Amidst varied opinions and misconceptions, companies and organizations are uncertain how the AI Act will affect them. So, what does the AI Act do exactly? Does it do it well? And what can other jurisdictions drafting AI legislation learn from the EU’s approach to AI regulation?

What is covered under the AI Act?

The AI Act primarily targets ‘AI systems.’ These are physical products or software applications that are built around or on top of a core AI model. The AI Act defines an AI system as:

“A machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.”

Is an elevator an AI system? Under a strict reading of this definition, it might be. However, the AI Act always asks us to consider AI systems in the context of their ‘intended purpose’ – roughly, the application envisaged by the developer. This contextual nuance should help prevent the AI Act from applying to everything that runs on a chip and hone in on the most risky use cases. The one place where the AI Act mentions ‘AI models’ rather than their overarching ‘AI systems.’is when it deals with general-purpose AI models (often called foundation models), a very important exception discussed later in the article.

Providers wishing to bring an AI system to the EU market must comply with the AI Act, regardless of their location. This means the AI Act has an extraterritorial impact. Since the EU is the world’s largest single market, few developers will want to miss out on it. EU officials hope these economic incentives spur a so-called Brussels Effect, where the EU effectively sets the global standard.

What does the AI Act do?

The AI Act’s overarching approach is not only context-dependent, it is also risk-based. The Act categorizes systems into lower and higher-tier risk classes, and regulates them accordingly. Within this risk-based framework, the AI Act does four main things:

- It prohibits certain AI systems. Systems that are very risky and which show very limited upside are categorically banned from the EU market. These prohibited AI systems include social scoring AIs and discriminatory or manipulative AIs.

- It imposes rules for high-risk AI systems. Some AI systems have the potential to bring about great benefits, but can also cause great harm when deployed without care. Such high-risk systems, used in critical infrastructure, education, recruitment, law enforcement, or medical devices, must meet stringent requirements under the AI Act. These include risk management, data governance, record keeping, drawing up technical documentation, and ensuring human oversight, accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. If a company brings to market an AI system that can grade high school exams, it must be ready to show it’s safe, unbiased, and otherwise respectful of human rights.

- It regulates general-purpose AI models. When the AI Act was written, regulators noticed a problem: not all AI systems have an intended purpose. AI systems such as ChatGPT can be used in a variety of contexts, and new use cases are found every day. However, through their rapidly increasing capabilities and applicability, they can also cause large-scale harm. After intense debate, the EU decided that general-purpose AI must be regulated at the underlying model level and not at the system level. Again, the Act differentiates based on risks here. All general-purpose AI providers must comply with a set of transparency requirements. Providers of more risky and compute-intensive models also face requirements to prevent negative impacts on public health, safety, security, human rights, or society.

- It creates governance structures. The AI Act finally creates the necessary governance structures, procedures, and standards to enforce the above-mentioned requirements. It delegates most enforcement tasks to the ‘competent authorities’ in individual member states. General-purpose AI regulation is to be enforced by a new, central EU authority called the AI Office.

What should we make of these rules?

The AI Act is a solid start. There are many lessons to draw for other jurisdictions considering or drafting AI regulation.

- Prohibit certain types of AI systems. Few people want to be assigned a social credit score that determines whether they can take the bus. It’s a show of no-nonsense mentality that the EU chose to draw moral ‘red lines’ for such systems and leave little room for gradual erosion of social norms. Prohibitions are simple and powerful options, and other jurisdictions considering or drafting AI regulation should not only follow suit, but add more bans, including for autonomous killer drones and automated decision-making in the context of migration.

- Set minimal requirements for the use of AI models in delicate sectors or products. Incidents like the Dutch childcare benefit scandal make it abundantly clear that we need checks and balances against unsafe or biased AI use in high-stakes settings. Through these minimal requirements, the EU can not only prevent harmful deployment, but also help shape the development trajectory of the technology towards more human-centric AI systems.

- Regulate general-purpose AI. Downstream providers building on foundation models have limited control over their systems’ behaviors as outcomes are largely determined by a black box motor block, trained by the primary provider. Moreover, the number of general-purpose AI applications will likely grow faster than enforcement agencies can keep up with, as each single general-purpose AI model can be used in hundreds of more specialized systems. These arguments have always been strong. However, so were the lobbying efforts against regulation at the model level. We should applaud the EU here for holding firm.

- Take a pragmatic classification approach to risk. Differentiating between lower and higher-risk use cases minimizes the chance of overregulation. In the case of general-purpose AI models in particular, the EU did well to follow a pragmatic classification approach based on compute thresholds. Any general-purpose AI model trained using more than 10^25 floating point operations (abbreviated FLOP, a measure of the total compute used) is presumed to belong to the higher-risk class. This is the most ambitious compute threshold to date, exceeding that of the U.S. Executive Order’s 10^26 FLOP threshold. While this classification mechanism may be imperfect, it is also the best currently available.

Despite these positives, the regulation has serious shortcomings – as might be expected for a first-of-its-kind policy. The AI Act risks becoming a paper tiger due to unclear rules and enforcement capacity that is severely lacking on multiple fronts. Furthermore, the requirements for the most compute-intensive general-purpose AI models show glaring loopholes and could become outdated before they even take effect. To future-proof the AI Act, the EU needs clearer rules, a new enforcement paradigm, and additional guardrails for next-generation general-purpose AI models.

How does the AI Act fall short?

Clear and actionable rules can foster the adoption of AI tools in sensitive sectors by reassuring users those tools are legal and safe to use. Moreover, ambitious requirements can provide the market with signals needed to spur innovation or to change the technology’s trajectory. The EU’s climate regulations are a great example of regulation boosting progress in energy efficiency and decarbonization. On the other hand, rules that are too complex or not specific enough can lead to legal uncertainty, spotty implementation, and arbitrary enforcement, thereby harming innovation and failing to protect fundamental rights.

As of yet, the AI Act’s requirements for high-risk systems lack the necessary clarity and actionability. To give just one example, high-risk systems must be ‘effectively overseen by natural persons during the period in which they are in use.’ What this requires in practice from providers or professional users is far from evident.

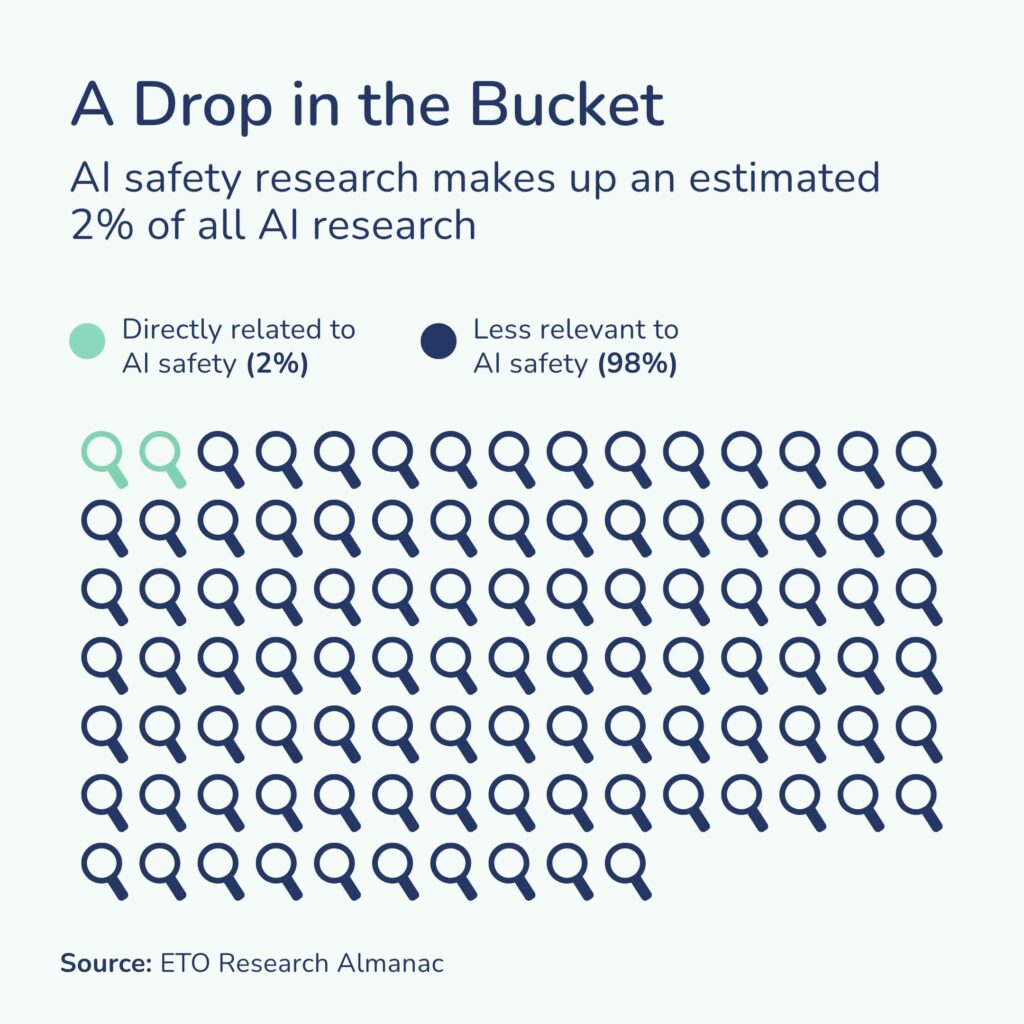

High-risk systems will typically run on specialized or fine-tuned models and will often be developed by smaller players who are not in a position to handle regulatory uncertainty. The EU has already missed the boat on general-purpose AI models as a result of insufficient and scattered investments. If the EU wants to be an innovator and not only a regulator, it has to double down on supporting research and innovation of AI applications that are less compute-intensive to train. AI can improve education by providing personalized teaching, promote health outcomes by speeding up medical diagnoses, or lead to more efficient power grids. To seize these upsides, the EU’s regulatory landscape must be seen as a business opportunity and not as a bureaucratic quagmire.

Outcomes are not set in stone, however. The clarity and actionability of the AI Act’s high-risk requirements will depend significantly on the standards that are currently being spearheaded by the European Standards Organizations. These standards will elaborate on the Act’s main legislation and should translate vague requirements into actionable guidelines. National representatives, industry associations, and civil society organizations are allowed to contribute to the standardization process. These parties play a crucial role in ensuring risks are mitigated without harming innovation.

So far, however, progress on standards has been very limited. Insiders have privately expressed worries that standardization won’t be finished in time and that the results are at risk of staying too abstract. The EU urgently needs more capacity and resolve to give standard-setting the attention it deserves. Unless it does, the continent is sleepwalking towards AI irrelevance.

How can it be improved?

Clarity and actionability are also paramount to effective enforcement. Without them, enforcement actors must continually question their judicial basis and can’t make concrete demands. The distributed nature of enforcement may not help here either. The AI Act delegates enforcement of the requirements for high-risk AI systems to individual member states’ competent authorities. These enforcement agencies will have to quickly gather the legal technical expertise to evaluate an increasingly large number of high-risk AI systems. For member states, especially the smaller ones, this will be a daunting task. Many experts have warned that without sufficient enforcement capacity, the AI Act loses its teeth and opens the door for uneven and unsubstantial enforcement.

A new enforcement paradigm

As the EU’s tech policy landscape increases in volume and complexity, central enforcement and coordination will become increasingly important. Such central capacity would have to be agile in nature, looking more like a start-up within government than a classic administration. It is thus disappointing to see that the EU did not follow the guiding example of the UK’s AI Safety Institute. While the UK managed to attract top-notch technical talent by creating a culture that enabled rapid progress and adaptability, the AI Office looks more like a rebranding of existing units in the European Commission.

For the AI Office to be effective, it has to be able to decide and act on much shorter timescales than are common in EU policymaking. This will require strong leadership that dares to tread outside conventional territory and is able to make difficult but necessary trade-offs. The rewards of such a culture shift could be great. If successful, the AI Office could expand its central capacity in a phased manner, taking a larger role in the enforcement of the Act’s rules for high-risk systems, or even become the nucleus of a nimble and fully independent digital enforcement agency, spanning several digital agendas. Such a future is now far away.

While the EU’s enforcement of general-purpose AI models is in a better place than its enforcement of high-risk systems, there’s a lot of work to do. In order to properly evaluate compliance with general-purpose AI regulation, the AI Office will need to hire a significant number of technical experts who have hands-on experience with frontier models. This kind of expertise is highly sought-after, and private companies offer up to 10x more compensation for technical roles than the AI Office. The EU urgently needs to increase its ambition to hire cutting-edge technical experts, even if that implies large internal salary discrepancies. There is also more opportunity to work together with academia, civil society and emerging organizations in the AI assurance space to draw on external capacity. Even if these suggestions are adopted, the AI Office’s capacity will likely be temporarily constrained. If so, it should prioritize enforcement of the riskiest models first, which will generally be those trained on the largest compute budgets.

Finally, the EU’s enforcement agencies need to learn to skate where the puck is going. Developments in AI are moving at a pace that no longer permits a purely reactive attitude. The European Commission should, therefore, create a dedicated AI foresight unit within the AI Office. This unit can help prepare for future AI challenges, working with outside experts and foresight practitioners. Studying compute trends in AI would enable this unit to discern several quantitative scenarios of compute budgets and AI capabilities. Building on those scenarios, the AI Office can ground their hiring strategy, and prepare for evaluation of new types of risks posed by general-purpose AI models yet on the horizon. It is disappointing to see that the AI Office missed the initial opportunity to include such a unit, ignoring the advice of several EU heavyweights in the AI space. However, there is still time to extend the Office’s set of tasks.

Next-generation general-purpose AI requires next-generation safeguards

Perhaps the most urgent shortcoming of the AI Act is that it could fail to keep citizens safe from next-generation general-purpose AI models. These models could introduce entirely new types of large-scale risks that can only be mitigated through external evaluations and pre-development guardrails – requirements that haven’t yet made it into the AI Act.

The AI Act refers to frontier general-purpose AI models such as GPT-4, Google Gemini, and Claude Opus as ‘general-purpose models with systemic risk’. Deployment of such models requires additional stress testing, assessment and mitigation of systemic risks, incident reporting and cybersecurity measures. Although the AI Office will further specify these rules in codes of practice, we already know that they will rely entirely on self-reported risk mitigation.

Frontier AI companies have to red-team and evaluate their own models, and self-check their own cybersecurity. They then have to report their findings to the AI Office. If an AI company fails to properly self-regulate, the AI Office can demand access to the model for external evaluation. Based on this evaluation, the company may be required to take additional mitigating measures. The AI Office can also issue fines or, in the worst-case scenario, force the removal of the model from the EU market.

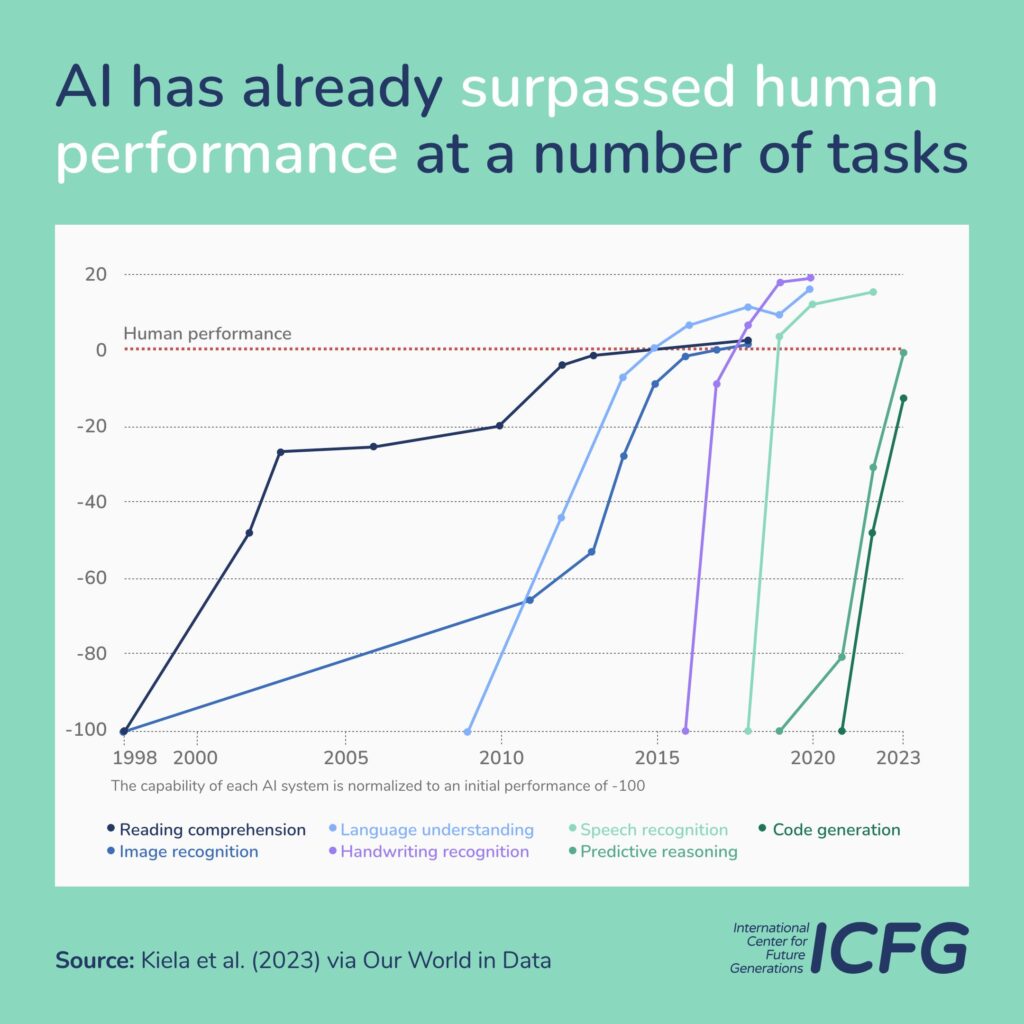

This corrective approach will likely suffice for current-generation models. Although today’s frontier models like GPT-4 show capabilities that sounded like sci-fi a couple of years ago, their inherent potential for harm is still relatively familiar. Today’s models are quite fragile, mostly incapable of planning out long, complex tasks, and typically don’t possess more dangerous knowledge than can be found using a Google search.

But AI capabilities are progressing at a breakneck pace. In just a few years, language models have moved from cute gimmicks to productivity-enhancing tools that help millions of users brainstorm, draft reports, or write programming code. Remarkably, this surge has been reasonably predictable, as new capabilities largely emerge from exponential increases in computing power used to train advanced AI systems.

This trend is unlikely to halt soon. For example, OpenAI and Microsoft are reported to have begun planning the build-out of a 100 billion USD AI supercomputer ominously called ‘Stargate’. This massive cluster could be operational as soon as 2028 and could be used to train models up to 100,000x more compute-intensive than GPT-4. But we may not need to wait until then. GPT-5 is rumored to be released by the end of 2024, and systems released in 2025 or 2026 could already prove transformative to the global economy. They could also pose new risks, such as meaningful assistance in the creation of man-made pandemics or large-scale accidents resulting from developers’ poor understanding of their systems’ inner workings.

Such risks emerge from a common loophole: the AI Act lacks third-party oversight, both in the pre-development and pre-deployment stage, which is especially concerning for advanced AI models. Big AI companies cannot be left to self-evaluate their own operational risks against people’s safety and human rights—they literally cannot evaluate such risks on their own as there is no science of “safe AI” to date.

If this loophole remains, and AI companies fail to implement their own robust infosecurity measures during the pre-deployment phase, their models could be stolen, for example by hackers, criminals, or rogue states. Leading AI companies already report having to defend against cyber attacks from increasingly well-resourced actors and admit their current cybersecurity is poor. Stolen models can have safeguards removed, potentially leading to unprecedented disinformation or automated cyber-attacks. And when the cat is out of the bag, there’s no way to get it back in.

Although lacking info security is just one of the potential failure modes, this example illustrates that the next generation of general-purpose AI models will require next-generation guardrails. With large-scale risks in plain sight, the EU must future-proof the AI Act’s general-purpose AI rules by obligating third-party evaluations in both the pre-development and pre-deployment stage. Such evaluations can assess whether the AI company has taken sufficient info security measures, make sure the AI company’s technical alignment plans are sufficient given the expected model capabilities, and check for the emergence of dangerous capabilities during training.

OpenAI spent 100 million USD to train GPT-4. Surely companies with budgets that large are also able to accommodate these reasonable oversight requirements to ensure their models serve the public interest.

General-purpose AI models have the potential to truly transform our economy, help society solve its largest problems, and usher in a new wave of prosperity that we can choose to distribute more fairly. When we don’t prevent large-scale harms or accidents, though, this transformation could be nipped in the bud. Next-generation general-purpose AI models could be released as early as December 2024, before the AI Act’s rules even take effect. It may seem strange to update a regulation before it applies, but the pace of change in AI calls for unconventional measures.

Conclusion

The European Union’s AI Act is a solid start but far from complete. To future-proof the Act, the EU should act now to:

- Develop clear and actionable standards and guidelines in dialogue with experts, industry, and civil society.

- Invest in more agile and centralized enforcement capacity, with world-leading technical expertise and a dedicated foresight unit.

- Expand the Act’s general-purpose AI regulation with mandatory external evaluations and pre-development guardrails for next-generation models.

Other jurisdictions considering and developing AI regulation should pay heed to these lessons. It’s easy to overlook enforcement, keep rules too vague in an attempt to keep legislation flexible, or to underestimate the exponential pace of change with AI. Whether the AI Act becomes a regulatory exemplar or a cautionary tale is still undecided. Legal clarity, careful implementation, effective enforcement, and forward-looking regulatory diligence will tell. The one thing that’s certain, however, there’s no time for complacency.

Originally published by Tech Policy Press