The AI Safety Institute Network: Who, What and How?

Alex Petroupoulos | September 2024

Executive summary

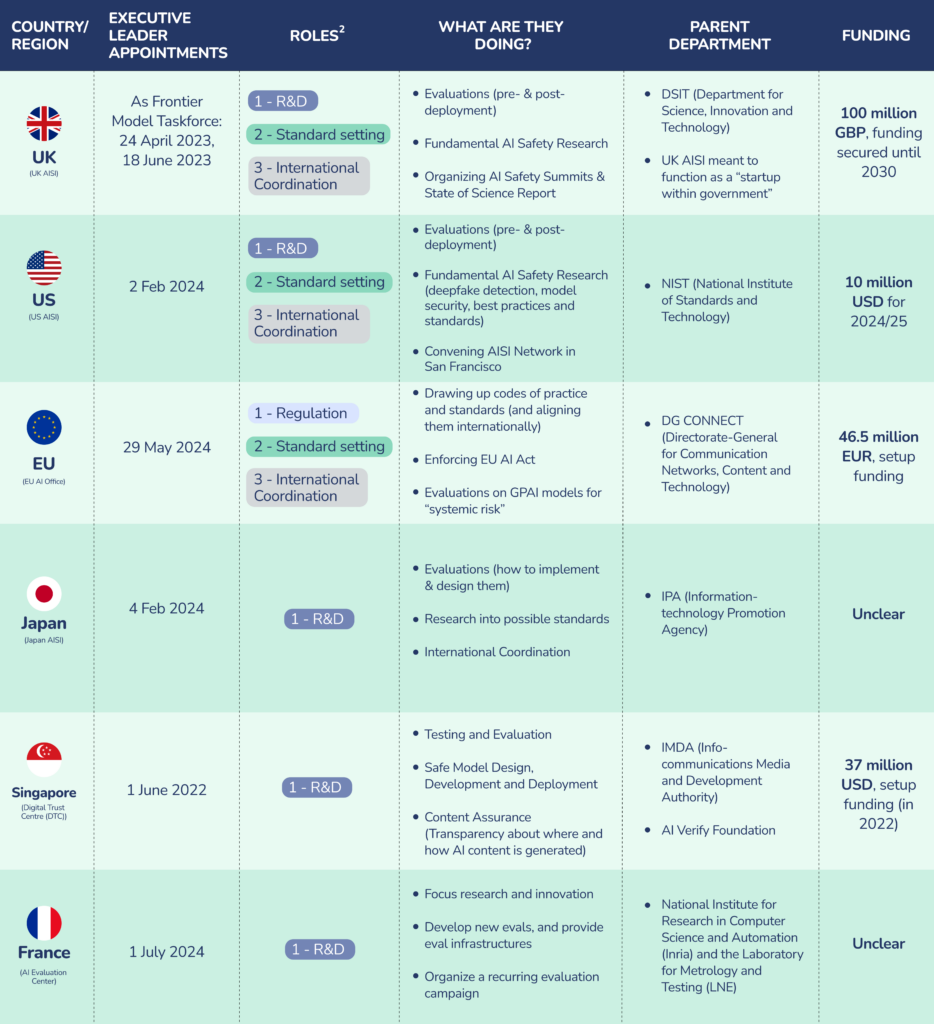

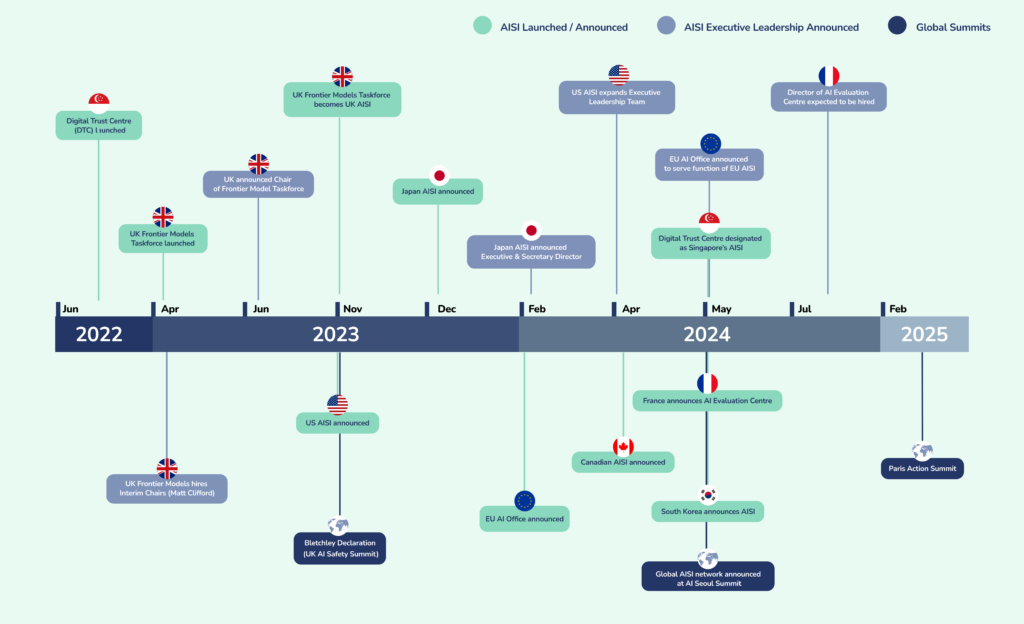

Following the Seoul AI Safety Summit, we have seen the announcement of a substantial network of state-run AI Safety Institutes (AISIs) across the globe. What progress has been made? How do their plans and motivations differ? And what can we learn about how to set up AISIs effectively? This brief analyses the development, structure, and goals of the first wave of AISIs1.

Key findings:

- Diverse Approaches: Countries have adopted varied strategies in establishing their AISIs, ranging from building new institutions (UK, US) to repurposing existing ones (EU, Singapore).

- Funding Disparities: Significant variations in funding levels may impact the relative influence and capabilities of different AISIs. The UK leads with £100 million secured until 2030, while others like the US face funding uncertainties.

- International Cooperation: While AISIs aim to foster global collaboration, tensions between national interests and international cooperation remains a challenge for AI governance. Efforts like the UK-US partnership on model evaluations highlight potential for effective cross-border cooperation.

- Regulatory Approaches: There’s a spectrum from voluntary commitments (UK, US) to hard regulation (EU), with ongoing debates about the most effective approach for ensuring AI safety while fostering innovation.

- Focus Areas: Most AISIs are prioritising AI model evaluations, standard-setting, and international coordination. However, the specific risks and research areas vary among institutions.

- Future Uncertainties: The evolving nature of AI technology and relevant geopolitical factors create significant uncertainties for the future roles and impacts of AISIs. Adaptability will be key to their continued relevance and effectiveness.

This brief provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of the AISI Network, offering insights into the challenges and opportunities in global AI governance. It serves as a foundation for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders to understand and engage with this crucial aspect of AI development and regulation.

Introduction

Why was the AISI Network Created?

“Coming together, the network will build “complementarity and interoperability” between their technical work and approach to AI safety, to promote the safe, secure and trustworthy development of AI. This will include sharing information about models, their limitations, capabilities and risks, as well as monitoring specific “AI harms and safety incidents” where they occur and sharing resources to advance global understanding of the science around AI safety.” – UK DSIT, Seoul Safety Summit

According to the agreement made in Seoul, all countries and regions creating AI Safety Institutes in the network do so “to promote the safe, secure and trustworthy development of AI”. What that actually means and how their institute should function is very much up to the interpretation of each.

Overall, the AISIs are working on evaluating frontier models, drawing up codes of practice and common standards, and leading international coordination on AI governance. The desire of each country to shape international AI governance according to its own vision has led to positive competitive dynamics with AISIs being set up across multiple countries. It should be noted, however, that speed isn’t everything. Anecdotally, some labs told ICFG that they have chosen to work with the UK AISI because they did the best work, rather than the fact that they were the first movers.

The AISIs of the UK, US and Japan, as well as the EU AI Office, have committed to evaluating Advanced AI models and have expressed concern over severe risks future advanced AI systems could pose, including the exacerbation of chemical and biological risks, cybercrime, and humanity’s potential loss of control over smarter-than-human AI systems.

In particular, at Seoul AI Safety Summit, participating countries and AI companies agreed “to develop shared risk thresholds for frontier AI development and deployment, including agreeing when model capabilities could pose ‘severe risks’ without appropriate mitigations.” These thresholds will be confirmed at the French AI Action Summit in February 2025, so the clock is ticking on identifying how to design and where to set these thresholds. This is an open technical problem that will require technical research and understanding and creates a common deadline that all AISIs now share.

However, some of these institutions, like the EU AI Office and the Singaporean DTC, have a wider scope and therefore have to balance safety with competing interests, like driving innovation and AI adoption. Furthermore, the EU AI Office, unlike the national AISIs, is tasked with the enforcement of hard law, namely the EU AI Act, which contains regulation of advanced AI. Also, stated goals for some institutes may differ from their visible actions.

Many of the AISIs are still in early setup stages. The existing public work is limited to public evaluations from the UK AISI, the drafting of codes of practice and broad-stroke international coordination. Many questions still remain about what the AISI network will look like in practice – until more work is done, it is impossible to be completely certain. However, we can observe some general trends emerging based on the public information available.

How is the AISI Network taking shape?

Some AISIs, like the UK AISI, have been built from the ground up, taking modern approaches to how public institutions can be staffed and run in a flexible and startup-like manner, inspired by learnings from the COVID pandemic. Others, like the US and Japan, are also building institutes from the ground-up, albeit slower.

Other AISIs have been created by expanding existing institutions, or institutions with other remits, to also include AI Safety. This approach can be more comprehensive, but also more bureaucratic and resource-intensive. The EU AI Office is a prime example of this, evolving from existing EU mandates and institutions, and inheriting a regulatory agenda on AI that started before generative AI entered the public eye. However, evolving out of existing institutions doesn’t necessarily lead to a slow start. Singapore has taken a similar path to the EU, also starting from a model that was developed in 2019 and in contrast to the EU, has already achieved outputs such as red-teaming a frontier model.

This difference in approaches mirrors two different AI governance strategies: a reactive one versus a proactive one3.

The first approach aims to keep up to date with fast-paced and uncertain technological advancements. Its response to a high-uncertainty environment is to lower the uncertainty window by gathering as much information as possible on the direction and progress of the technology.

The second approach aims to preemptively and actively steer the development of the technology in a fixed direction.This approach responds to a high-uncertainty situation by instead focusing on one specific outcome in mind, ahead of time, and laying out a plan to achieve it.

These methods come with tradeoffs. The reactive approach could fail to prepare for certain risks or act in time, thus exposing businesses and the general public to otherwise avoidable harms. However, the proactive approach risks wrongly anticipating either the direction that technology could go, or the risks that could end up actually mattering most, or, crucially, pushing technology or solutions in suboptimal directions.

In an ideal world, regimes would start off in the reactive mode, but with the ability to rapidly shift to the proactive model once uncertainty was sufficiently low and more information was available. Importantly, starting in a reactive mode doesn’t mean that states shouldn’t be taking any action right now. Rather, it means that the type of action they should be taking is action that enables them to:

- gather more information so that they can shift from reactive to proactive sooner, and

- be able to quickly and effectively shift from reactive to proactive when that moment comes.

These factors are examples of building state capacity, and we can directly study AISIs being set up as an exercise in building state capacity. Importantly, they don’t have to exist as an institution that will carry out proactive action. Rather, they can act as an enabler of that transition between a more reactive regime and a proactive one.

Both reactive and proactive models of AI governance have the potential to be successful even if limited by institutional or bureaucratic constraints. Regardless of which model a regime decides to choose, embracing the factors that bring it closer to the ideal model are most important. Reactive regimes benefit from building up capacity to quickly act in the future, even if they don’t act now. And proactive regimes benefit from holding onto flexibility and the ability to adjust and adapt their schemes as new information becomes available.

Methodology

Research primarily consisted of desk research, backed by a series of semi-structured interviews with staff at various AISIs or other researchers studying AISIs.

This brief provides a comprehensive analysis of the AI Safety Institute (AISI) Network by examining individual AISIs across several key dimensions. For each AISI, we explore two main areas:

- Background

- Historical context and events leading to the establishment of the AISI

- Key dates and milestones in the AISI’s development

- Institutional setting and parent organisations

- Initial funding and resource allocation

- Vision

- Stated goals and objectives of the AISI

- Core focus areas and priorities

- Planned activities and initiatives

- Approach to AI safety and governance

- Key statements from leadership reflecting the AISI’s mission

This approach allows for a systematic comparison across different AISIs while acknowledging their unique contexts and approaches. By consistently applying this framework, we can identify common themes and divergent strategies.

The brief covers the AISIs or equivalent institutions of the UK, US, EU, Japan, Singapore, and France in detail, with brief mentions of other countries’ efforts where information is available. These AISIs were chosen as they are, at time of writing, the most advanced and therefore provide the most useful evidence base for the identification of best practices and key features for successful AI governance, providing valuable insights for governments who have not yet established their AI governance strategies or institutions.

Some questions unanswered by this brief are why the AISIs have their goals and exploring what they will need to do to properly internationalize the AISI network. This could be future work done by ICFG, other organizations, or a collaboration of both. Also, while other research conducted on AISIs backs up many of the findings, the AISI network is still in its infancy, so assessing outcomes is challenging.

AISI Country Overview

Click on each country name to learn more about their respective AI safety institutions.

Background

Despite not being an AISI nominally, at the AI Seoul Summit the EU confirmed that the EU AI Office would perform the role of the EU’s AISI. The AI Office was created first and foremost for the purpose of enforcing the EU AI Act.

Although discussions about an EU AI Office date back to the early days of the EU AI Act’s conception (as early as 2020), the AI Office only launched on 21 Feb 2024, 10 months after the UK AISI. On 29 May 2024, the EU announced the leadership and structure of the AI Office, with Lucilla Siolli leading it. This announcement of leadership comes 4 months after the US announcement and a year after the UK’s.

The announcement also leaves two key posts unfilled, the Lead Scientific Advisor and Head of Unit on AI Safety. These three positions will be crucial for the AI Office carrying out its safety-related tasks and fitting into the global network of AISIs.

The AI Office’s initial budget was €46.5 million, reallocated from existing budgets.There are five units in the AI Office, with 140 staff planned to be spread between them. They are:

- Regulation and Compliance Unit

- AI Safety Unit

- Excellence in AI and Robotics Unit

- AI for Societal Good Unit

- AI Innovation and Policy Coordination Unit

It should be noted that this structure is mostly a repurposing of existing units within the Commission.

These units came into effect on 16 June 2024. Note that AI Safety only makes up one of the Office’s 5 units. How these priorities will be weighted will only be clear once staffing has been fully allocated, but the Regulation and Compliance Unit will necessarily require significant manpower to handle the EU AI Act’s GPAI rules – on top of existing EU digital legislation. With over 86 different EU laws currently affecting the digital sector (and 25 more planned), navigating what decisions are under their jurisdiction will be a key challenge.

While there is, anecdotally, ambition from AI Office’s staff to move quickly and learn from the UK and US AISIs, they may be limited by existing EU rules and procedures. The formal timeline will see the first technical hires only by November 2024, 9 months after launching. There is some uncertainty here, as the Office may also be hiring faster outside of this official channel, via headhunting or direct hires. There is precedent for that. The UK AISI, for example, had both a slower official hiring process, as well as an expedited, more flexible, less official stream.

The two upcoming deadlines for the AI Office are:

- May 2025 – GPAI Codes of Practice for the AI Act due

- August 2025 – GPAI provisions of EU AI Act take effect

As of the Seoul AI Safety Summit, there is one additional deadline. At the Summit, participating countries and AI companies agreed to decide on risk thresholds, beyond which companies would not be able to scale or improve their models without first implementing sufficient precautions. The details of those thresholds were left to be decided at the next Summit, on the 10 Feb 2025 in Paris. The clock is now ticking on figuring out where those thresholds should be set. This is an open technical problem that will require technical research and understanding.

The EU AI Office is being set up at the pace to meet its May 2025 deadline. In order to meet the new February 2025 deadline, it may need to move faster.

Vision

The EU AI Office aims to:

- Support the AI Act and enforce general-purpose AI rules

- Strengthen the development and use of trustworthy AI

- Foster international cooperation

- Cooperate with existing institutions, experts and stakeholders in AI governance

Together with developers and a scientific community, the office will evaluate and test general purpose AI to ensure that AI serves us as humans and uphold our European values – Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age

The EU AI Office will evaluate advanced AI models for systemic risks and ensure that they comply with additional requirements set out in the EU AI Act. It will also guide international coordination, including developing codes of practice for compliance with the EU AI Act.

Any general purpose AI (GPAI) models trained on more than 10^25 FLOP are considered to come with “systemic risk” and will have to comply with additional provisions under the AI Act. It’s the EU AI Office’s job to evaluate advanced AI models for systemic risks and ensure that they comply with the additional requirements.

In addition to enforcing the AI Act for advanced AI models, the Office also has the goal of encouraging the adoption of AI technologies across the EU and EU institutions.

“[The EU AI Act] focuses regulation on identifiable risks, provides legal certainty and opens the way for innovation in trustworthy AI.” – Ursula Von Der Leyen

Like several AISIs, the EU AI Office also aims to shape international coordination. One example of this are the codes of practice for compliance with the EU AI Act. While industry groups and civil society organisations from around the world are involved in designing them, they ultimately represent an EU effort to promote its vision of international AI governance through a “Brussels effect”. This takes the form of both other jurisdictions directly copying EU codes of practice and the AI Act’s risk framework, or the de facto extraterritorial implications of the AI Act applying to any company that operates in the EU, regardless of origin.

More recently, EU countries aligned with the UK and US to recognize the severe national security risks that advanced AI models could potentially pose. These include capabilities to cause chemical and biological risks, as well as loss of control risks (related to AI deception and autonomous replication).

Background

On 22 May 2024, France announced plans to open a new AI Evaluation Center. This center is a partnership between two established institutions:

- The French National Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation (Inria): A public science and technology institute under the joint authority of the Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation and the Ministry of Economy, Finance, and Recovery.

- The Laboratory for Metrology and Testing (LNE): The French national agency responsible for designing technical standards, analogous to NIST in the US.

The chief executive of the AI Evaluation Center was expected to start their new position on 1 July 2024. As of early July, no information has been released about who has filled this role, or if it has even been filled yet.

Vision

The AI Evaluation Center aims to become “a national reference body for evaluating all types of AI systems (software solutions or embedded systems, various industrial application sectors).” The Center has three primary objectives:

- Focus research and innovation on AI Safety

- Develop new tests and test infrastructures for systems under the EU AI Act’s scope

- Organise a recurring evaluation campaign of GPAI models

“A profoundly new place, the AI Factory, will host a new AI evaluation center and aims to become one of the world’s largest centers for AI model evaluation, in line with the AI Act.” – Emmanuel Macron

Macron aims to have the AI Evaluation Center host a branch of the EU AI Office, to provide the Office technical expertise for model evaluations. Like Singapore’s DTC, the AI Evaluation Center will mostly focus on R&D, while other parts of Europe’s AI Governance structure, such as the AI Office, will handle international coordination and standard setting.

The Center’s creation aligns with Macron’s vision of Paris becoming “the city of artificial intelligence.” However, he has also emphasised a European approach: “Our aim is to Europeanise it [AI], and we’re going to start with a Franco-German initiative.“

“France aims to establish a structure that enables everyone to work together. There is the UK Safety Institute, the US Safety Institute, Korea, and Taiwan. So, it’s not about everyone working on the same subject in parallel. It’s about avoiding wasting time by doing the same thing multiple times. The idea is to divide tasks so that everyone works together concertedly on these subjects. It’s pointless for France, for example, to have different regulations from others.” – Stéphane Jourdain, Head of the Medical Environment Testing Division at LNE, 27 May 2024

Background

The Japanese AISI was announced in December 2023, following the UK AI Safety Summit, and launched in February 2024. On 14 February 2024, the Japan AISI announced its executive leadership, with aims to reach a staff count of several dozen people. However, a target date for reaching this intended staff count has not yet been announced.

In April 2024, the Japanese ministries of Internal Affairs and Communications and the Ministry of Economy released the initial draft of their AI Business Guidelines. This framework was designed to provide advice to businesses and potentially shape future AI regulations. The guidelines were developed based on discussions held at the “AI Network Society Promotion Council” and the “AI Business Operator Guidelines Study Group”, as well as a public consultation for invited comments held in early 2024.

These guidelines include recommendations for AI developers on documentation and transparency, as well as contributing to research on AI quality and reliability and ethical and responsible development guidelines.

Vision

While the exact risks the Japanese AISI will focus on are not yet clear, their mitigation strategies are taking shape. Like the UK AISI, the Japan AISI will primarily focus on three main areas:

- Safety research (e.g., cybersecurity, AI standards, testing environments)

- Evaluations

- International coordination

“You can’t step on the accelerator without a brake. It is dangerous to think only about promoting AI.” – Akiko Murakami, Director of Japan AISI

The Japanese AISI’s vision encompasses several key activities:

- Standards collaborations: The Japan AISI has already begun working with NIST and the US AISI on aligning their AI standards.

- Evaluation research: Ongoing research into evaluations, drawing inspiration from similar efforts by Singapore and the UK.

- International coordination: Building upon existing actions, including the Hiroshima AI Process, which kicked off in May 2023 following the Hiroshima G7 Summit. This process resulted in the Hiroshima AI Process Comprehensive Policy Framework in October 2023.

- Information dissemination: Working with both industry and academia to raise awareness of AI safety through seminars and educational material.

- Global collaboration: Participating in various summits, workshops, and roundtables, and engaging in bilateral and multilateral conversations on shared frameworks and standardisation procedures.

Background

On 22 May 2024, Singapore announced that its Digital Trust Centre (DTC) would be transformed into Singapore’s AISI. However, Singapore’s AI Governance efforts preexist this announcement, with the DTC playing an AISI-like role since at least January 2024.

Key milestones in Singapore’s AI governance journey include:

- 23 Jan 2019: Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPD) released the first edition of its Model AI Governance Framework for consultation.

- 21 Jan 2020: PDPD released the 2nd edition of the Model Framework. The PDPD is a sub-agency of the Info-communications Media and Development Authority (IMDA), Singapore’s authority for regulating and developing the infocomm and media sectors as well as fostering innovation, enhancing digital infrastructure and promoting digital literacy and inclusion.

- June 2022: The DTC was founded with a S$50 million (37 million USD) grant from IMDA and Singapore’s National Research Foundation (NRF). It was set up to “lead Singapore’s R&D efforts for trustworthy AI technologies and other trust technologies”, but it is unclear for how long its focus has been on generative AI systems and frontier AI models

- June 2023: IMDA launched the AI Verify Foundation, focusing on AI verification (meeting specifications) and validation (meeting expectations). This foundation brought together stakeholders from various sectors, including industry, academia, and government, to collaborate on creating a robust and trustworthy AI ecosystem. The AI Verify Foundation had a strong focus on building out testing infrastructure. Alongside the AI Verify announcement, IMDA also released a discussion paper analysing distinct risks that could be posed by generative AI.

- January 2024: IMDA and the AI Verify foundation released their Proposed Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI. This built on the previous Model Framework for traditional AI.

- 6 June 2024: Official Model Framework for Generative AI released.

“To keep pace with advancements in model capabilities, R&D in model safety and alignment needs to be accelerated. Today, the majority of alignment research is conducted by AI companies. The setting up of AI safety R&D institutes or equivalents in UK, US, Japan and Singapore is therefore a positive development that signals commitment to leverage the existing R&D ecosystem as well as invest additional resources (which could include compute and access to models) to drive research for the global good.”

– Singapore’s Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI, 6 June 2024

Within this framework, IMDA makes reference to the different AISIs being set up around the world and claims that the DTC is fulfilling a similar role to the AISIs of the UK, US and Japan in conducting “R&D in model safety and alignment”. These claims are then confirmed in the official Model Framework for Generative AI, released on 6 June 2024.

It therefore looks like the DTC has been playing its part within Singapore’s AI Governance structure as its AISI since at least January 2024.

Vision

The Singapore AISI, evolving from the DTC, aims to “address the gaps in global AI Safety Science“. Its focus areas include:

- Testing and Evaluation

- Safe Model Design, Development and Deployment

- Content Assurance/Provenance (Transparency about where and how AI content is generated)

- Governance and Policy

The Singapore AISI’s vision is rooted in the belief that demonstrating safety can drive innovation and adoption of new technologies in business. As stated in their Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI:

“Safety and Alignment Research & Development (R&D) – The state-of-the-science today for model safety does not fully cover all risks. Accelerated investment in R&D is required to improve model alignment with human intention and values. Global cooperation among AI safety R&D institutes will be critical to optimise limited resources for maximum impact, and keep pace with commercially driven growth in model capabilities

The DTC was primarily a Research & Development (R&D) institution, so it is expected that the Singapore AISI will retain that focus, matching the efforts of the UK and US AISIs on fundamental AI Safety research and evaluations.

It’s unclear whether the designation as the Singapore AISI will massively change the work the DTC does, beyond providing a clearer focus and allowing it to nicely fit in place with the existing international network of AISIs. As what was essentially a university-based research centre, its ability to engage in international coordination and match some of the other AISI’s domains may be limited, especially prior to being officially designated an AISI. However, these other domains may be covered by the other governance structures and institutions like IMDA and AI Verify.

The Singapore AISI is actively pursuing international & industry collaborations:

- Exploring potential collaborations with the US and UK AISIs on model evaluations.

- On 5 June 2024, the US AISI announced collaboration with the Singapore AISI on “advancing the science of AI Safety”.

- IMDA and AI Verify have partnered with Anthropic for a multilingual red-teaming project to collaborate on “a red-teaming project across four languages (English, Tamil, Mandarin, and Malay) and topics relevant to a Singaporean audience and user base.”

This makes Singapore only the second country to have publicly contributed to the evaluation and red-teaming of frontier AI systems.

Background

The United Kingdom founded one of the first national government institutions focused on advanced AI when it announced its Foundation Model Taskforce (FMT) in April 2023. This taskforce was inspired by the success of the UK Vaccine Taskforce, which accelerated the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines in the country. The Foundation Model Taskforce, later renamed the Frontier AI Taskforce, prioritised speed, talent acquisition, and information gathering.

By June 2023, the Taskforce was launched and had hired its permanent chair, Ian Hogarth.

In November 2023, following the UK-hosted AI Safety Summit, the Frontier AI Taskforce was transformed into the UK AI Safety Institute (UK AISI). This transition built upon the existing structure and priorities of the taskforce.

The UK AISI is centred around three main pillars:

- Moving Fast: Aiming to keep pace with rapid AI advancements.

- Hiring Exceptional Talent: Attracting top experts from the AI industry and academia.

- Focus on Empirical, Measurable Research: lowering uncertainty about AI risks

The initial taskforce format allowed a “startup”-like approach within government – still following existing accountability rules, but being able to operate and hire on much shorter timelines. The UK AISI inherited this startup-like character from its taskforce predecessor.

Political buy-in from the then Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, enabled the UK AISI to be set up in this manner to prioritise speed.

“In a world of rapidly moving technology, we believe the government can only keep pace if it can ship fast and iterate. “ – Ian Hogarth, Chair of UK AISI, 20 May 2024

The UK AISI made acquiring talent with experience working in frontier AI companies one of its Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Eleven weeks after the founding of the taskforce, it had already brought 50 collective years of frontier experience on board, which it expanded to 150 collective years by week 20.

The UK AISI’s initial budget of £110 million helped it recruit top talent. Fostering an institutional culture with somewhat increased flexibility and informality within the traditional civil service structures has also helped attract talent, especially from the existing tech startups and AI companies. In 2014, the Baxendale report listed Culture as one of the primary barriers to attracting talent in the Civil Service. In each of its progress reports, the UK AISI’s Chair has stressed that the fundamental reason the UK AISI exists is to make sure that UK policymakers have access to the best information possible on AI in general, not just on AI Safety. The UK AISI’s leadership hopes that by bringing top private-sector talent into government, the AISI team will advise and enable civil service to dynamically and swiftly draft proportionate and effective policy responses to a constantly changing, rapidly evolving technology. In other words, the ability to acquire and interpret information will allow for greater flexibility.

Vision

The Institute’s current focus areas include:

- Building and conducting evaluations to assess specific potential risks of advanced AI models, and helping others do the same

- Leading international cooperation on AI governance

- Creating the International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI

- Foundational AI Safety research

“Optimism does not mean blindly ignoring risks.[…] Building the capacity to empirically assess these risks so that policymakers are informed is critical. This is AISI’s core work.” – Ian Hogarth, Chair of UK AISI, 20 May 2024

The UK AISI aims to constantly monitor frontier AI systems by running evaluations and experiments on cutting-edge models, while also contributing to base-level AI Safety research. It also prioritises international collaboration, having organised the first AI Safety Summit in November 2023 and co-organizing the second summit with South Korea in May 2024.

The UK AISI focuses on risks from advanced AI models by designing and executing evaluations (tests performed on advanced AI models after and sometimes during their development) to collect empirical data about their ability to pose specific risks. By May 2024, the UK AISI had evaluated 5 state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) that are accessible to the public, assessing their ability to conduct cyber-attacks, and whether they possess expert-level knowledge in chemistry and biology that could cause harm.

AISI evaluators also examined whether the models could effectively act in an agentic manner, meaning they autonomously pursue set goals and multi-step plans with limited human supervision or intervention. The UK AISI also has a tentative plan to do further research on the evaluation of agents or agentic models, and on broader societal impacts of frontier AI.

The UK AISI is also working on AI safety research beyond just evaluations.

Finally, the UK AISI prioritises international cooperation on AI governance, and plans to foster international partnerships. In line with this goal, the UK AISI organised the first AI Safety Summit in November 2023 in Bletchley Park, UK, leading to the Bletchley declaration. With this first summit, the UK government succeeded in bringing the US and China into the same room to discuss international cooperation on AI governance. The UK AISI then co-organised the second AI Safety Summit with South Korea in May 2024 and commissioned the first International Report on the Safety of Advanced AI, significantly driving and shaping international cooperation on the governance of advanced AI.

The Institute also has the goal of spearheading a network of AISIs around the world with the goal to facilitate international research collaboration and information exchange between AISIs across national borders, with the goal of eliminating the need for AI companies to build relations with AISIs in every country they operate in. So far, the UK AISI has signed international partnerships with the US and Canadian AISIs, and has announced it will open a branch in San Francisco in Summer 2024 to attract and hire more US talent and enable better cooperation with US-based AI companies and the US AISI.

The international partnership with the US AISI paved the way for the UK AISI conducting pre-deployment safety evaluations on Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet model and sharing the results with the US AISI.

In April 2024, Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, commented that “You can’t have these AI companies jumping through hoops in each and every single different jurisdiction, and from our point of view of course our principal relationship is with the U.S. AI Safety Institute… I think everybody in Silicon Valley is very keen to see whether the U.S. and U.K. institutes work out a way of working together before we work out how to work with them.”

This indicates that the US-UK AISI agreement played an instrumental role in allowing the UK AISI pre-deployment access to evaluate Claude 3.5 Sonnet, given that Anthropic is a US-based company.

Background

The US AISI was announced in November 2023, following the UK AI Safety Summit. Despite being announced just one day before the UK AISI, it only announced its executive leadership on 2 Feb 2024, ten months after the UK AISI announced its own. This delay was due to the US AISI being set up from scratch, unlike the UK AISI which evolved from an existing taskforce.

The US AISI currently has $10 million funding through NIST as part of the 2023/2024 federal budget, which was approved in March 2024. President Biden has proposed a 2024/2025 budget that would allocate $65 million to support the US AISI’s mandate, which has yet to be approved.

These budgets run from 1 October to 30 September, but because of the complex nature of US federal budget approval, often end up being approved halfway through the year.

Vision

“Mitigating the safety risks of a transformative technology is necessary to harness its benefits.” – US AISI, 21 May 2024

The US AISI’s vision is “a future where safe AI innovation enables a thriving world”. To get to that future, they lay out a plan to mitigate AI safety risks. The US AISI’s three goals are to:

- Advance the science of AI safety;

- Articulate, demonstrate, and disseminate the practices of AI safety; and

- Support institutions, communities, and coordination around AI safety.

Like the UK AISI, the US Institute’s strategy includes a strong commitment to building out the science of measuring and evaluating the risks of Advanced AI. This science-led approach aims to develop and research best practices and assess risks before legislating.

This is no surprise, since the US AISI is based within the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST), an institution known for advancing the frontiers of “measurement through science, and science through measurement”. In other words, they believe that the best way to learn more and further science is by measuring, and that the process of measurement itself is improved and refined through scientific advancements, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

“AI safety depends on developing the science, but also on the implementation of science-based practices.” – US AISI 21 May 2024

The second aspect of the US AISI’s goals is the dissemination of best practices and support of other institutions and communities. The US AISI emphasises collaboration across industry, civil society, and international partners.

Through this collaborative approach, the US AISI has secured agreement from all major AI companies to provide access to their models for pre-deployment testing.

“We have had no pushback, and that’s why I work so closely with these companies,” – Gina Raimondo, US Secretary of Commerce, 07 June 2024

More recently, the US AISI signed memorandums of understanding with OpenAI and Anthropic that would give it formal model access both prior to and following the public release of major AI models.

“With these agreements in place, we look forward to beginning our technical collaborations with Anthropic and OpenAI to advance the science of AI safety,” Elizabeth Kelly, director of the U.S. AI Safety Institute.

Building on its agreement with the UK AISI, the U.S. AI Safety Institute plans to “provide feedback to Anthropic and OpenAI on potential safety improvements to their models, in close collaboration with its partners at the U.K. AI Safety Institute”.

The international network of AI Safety Institutes is central to the US AISI’s efforts. It plans to convene international AISI representatives in San Francisco later this year, where it recently opened offices. The US AISI also receives support from the US AISI Consortium, a group of over 200 academic institutions, corporate entities, non-profit and research organisations, and government and policy organisations.

Interestingly, the US AISI frames all of its safety interventions as boosting innovation in the long run.

“Safety breeds trust, trust provides confidence in adoption, and adoption accelerates innovation.” – US AISI 21 May 2024

While the UK plans to boost innovation by having its AISI lead to more proportional and effective regulations, the US AISI believes that safety in and of itself is a driving force of innovation, because it increases consumers’ trust in AI technology, increasing adoption, which drives innovation.

A national security lens is another core piece to the US government’s views on AI governance, with concerns about Advanced AI proliferating cyber risks and biorisks. After all, the US’s first major AI policy intervention was restricting the export of high-end AI chips to China, with national security concerns as the sole justification.

Canada and South Korea have announced AISIs, but there is still limited information available on them. Australia, Germany and Italy also signed onto the “network of international AISIs”, but have not announced any plans so far.

Critical exogenous factors

As the world rushes to set up AISIs, it’s useful to reflect on the successful models so far and the overlapping features, namely talent, speed and flexibility. Embracing these principles will be important for AISIs to succeed in their missions. However, beyond these attributes there is room for more work on what a network of AISIs should look like and how it can become more than the sum of its parts. ICFG is considering future research and collaborations on this topic. We are also working on resources to help policymakers and the public better understand the fast-moving developments on AISIs, starting with this brief and to be followed with an interactive timeline of AISI-related announcements.

Beyond the importance of the network design, there are other critical factors at play for understanding the role of AISIs in AI governance. At the end of the day, the AISIs will only guide regulation, not make it. The trajectory of national AI regulations and individual AISIs will be determined by the broader political environment they exist within – and two particular factors are worth exploring in the early stages of the development of AISIs.

Elections

For several of the countries mentioned above, 2024 is an election year. Changes in leadership could shift the international AI governance landscape by shifting national policy priorities and goals. Elections and their ensuing political support (or lack thereof) are a key input to an AISI’s speed, including resources.

- EU Parliamentary elections (6-9 June 2024) – It is uncertain how the EU’s approach to AI may change following this election. For example, the more right-wing post-election EU Parliament could lead to a stronger emphasis on the innovation or national security aspects of AI, rather than on consumer protections.

- UK General election (4 July 2024) – Incumbent Rishi Sunak (Conservative) was replaced by opposition leader Keir Starmer (Labour). Sunak was a strong supporter of the UK AISI, which has allowed it to operate at its expedited pace. In its manifesto, Labour has committed to ensuring the safe development of AI with binding regulation on the companies making advanced AI models. This is a move away from the current UK model which relies on voluntary commitments and the UK AISI pursuing strong working relationships with AI companies. The timeline, scope and direction of new regulation is unknown, but it could reflect a shift in strategy of the UK’s AI Safety efforts and possibly weaken UK AISI’s relationships with AI companies. At the same time, the measures could simply complement the existing work done by the UK AISI and act as a check against companies backing out of voluntary commitments.

- US elections (5 November 2024) – Polls place Democrats and Republicans at too-close-to-call margins for the presidency. It is also unknown how the US’s AI governance Agenda would change under a Trump presidency. With these factors combined, the November election makes the future of US AI governance highly uncertain. Along with the presidential election, large parts of Congress are also up for election. With Congress having control over NIST funding, this is another uncertain factor that will determine the trajectory of US AI governance.

Funding

One final aspect to touch upon is how the funding of the AISIs will contribute to their effectiveness and relevance. Funding is a key input to talent.

- The UK AISI is currently the most generously funded AISI, with over £100 million in initial investment, as well as commitments to maintain its yearly 2024/25 funding until 2030.

- The US AISI has a comparatively weak funding position, receiving $10 million in funding for 2024/25 through NIST. These funds are allocated on a yearly basis and largely determined by the makeup of Congress, making it more dependent on short-term political developments. The bi-partisan Senate AI Workgroup is trying to secure more substantial and stable funding for the US AISI and NIST.

- The EU AI Office’s initial budget was €46.5 million, reallocated from existing budgets. Given the AI Office’s legislative backing, it is expected that its funding will be stable, but the scope and scale of continued funding is unknown.

- The Canadian AISI has a comparatively modest, but stable funding situation for the next five years, with 50 million Canadian dollars being allocated to it as part of the 2024-2029 Federal Budget.

- The Singapore AISI is being created out of the DST, which had a S$50 million (37 million USD) setup grant in 2022. What remains from those setup funds is unknown.

Cross-cutting Observations in the AISI Network

While the AISI network is still in its early stages, several noteworthy patterns and potential implications have already emerged. This section presents cross-cutting observations based on the available information about various AISIs, highlighting key factors that may influence their development and effectiveness – trends that are particularly instructive for civil services in the planning process of launching a new AISI.

Structural Approaches and their Implications

New vs repurposed institutions

- Observation: Most countries (e.g., UK, US) have built AISIs from scratch, while others (e.g., EU, Singapore) have repurposed existing institutions.

- Potential Implication: New institutions may offer greater flexibility and speed, while repurposed ones may benefit from established processes and expertise. While Singapore has the newly established AI Verify foundation to provide flexibility, the EU only has the AI Office

- Observation: The EU AI Office serves as both an AISI and a regulatory body, unlike other AISIs that focus primarily on research and advisory roles.

- Potential Implication: This dual role may present unique challenges in building trust with AI companies while also enforcing regulations.

- Observation: There’s significant variation in funding, from the UK’s £100 million to the US’s initial $10 million.

- Potential Implication: These disparities may impact the relative influence and capabilities of different AISIs in the global network.

Operational Factors

- Talent Acquisition Strategies

- Observation: AISIs are employing various strategies to attract top talent, with some adopting more flexible, startup-like structures.

- Potential Implication: Success in attracting talent from the private sector and academia may significantly influence an AISI’s effectiveness and impact.

- Operational Speed and Flexibility

- Observation: AISIs built from scratch, like the UK’s, appear to be moving faster in operationalizing and producing outputs.

- Potential Implication: Speed and flexibility may be crucial factors in an AISI’s ability to keep pace with rapid AI advancements and maintain relevance.

While it’s too early to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of different AISI models, these observations provide a framework for understanding the current landscape and potential future developments. As the AISI network continues to evolve, ongoing monitoring and analysis of these factors will be crucial for assessing their impact on global AI governance and safety efforts.

The EU AI Office is not an AI Safety Institute

The analysis shows that the EU AI Office is an outlier among the network of AISIs being set up.

It is the only institution set up with regulatory powers, has the broadest scope of all the AISIs and is one of the few AISIs that has evolved out of an existing structure, rather than as a new institution set up from scratch.

This is possibly a symptom of the fact that the AI Office’s “Safety Institute duties” were handed to it by the Commission when the AISI network was announced, despite its original scope being focused on the EU AI Act. This after-the-fact designation of the EU AI Office as the EU’s AISI comes with limitations. While it makes sense to concentrate AI talent, the EU AI Office may be designed in a way that makes it challenging to pursue the work of an AISI.

These structural limitations may be limiting its ability to successfully function as an AISI. 81 days after it was founded, the UK AISI had released its first progress report, hiring over 50 years worth of frontier-lab technical expertise, bringing prominent AI researchers Yoshua Bengio onto it’s advisory board and hiring researchers like David Kreuger and Yarin Gal as research leads. 74 days into its setup, the US AISI had hired Paul Christiano as Head of AI Safety.

As of writing, it has been more than 104 days since launch (24 May 2024) and the EU AI Office still hasn’t hired a head of Unit for AI Safety, or a chief scientist. These are essential roles for the AI Office to act as the EU’s AISI.

These dates are already on the conservative end of the spectrum, starting from when each institution announced its senior leadership. If we instead count from when each institution was funded and announced, the AI Office is a further 40 days behind the US and an additional 80 days behind the UK, when it comes to announcing research leadership and heads of AI safety.

Using that metric, at this point in its setup the UK AISI had tripled its technical talent pool to 150 hours worth of frontier research talent, with major hires like Jade Leung from OpenAI and Rumman Chowdhury.

The EU AI Office’s outlier status raises serious questions of whether it can effectively fill its role as the EU’s AISI. It may be better for the AI Office to focus its efforts on the effective implementation and enforcement of regulations and to leave the risk assessment and safety work to some new institution. One vision for this could see a possible CERN for AI being established, which (being more science-focused rather than regulation-focused) would be able to better carry out the roles needed from the EU’s AISI.

Conclusion

The emergence of the AI Safety Institute (AISI) Network marks a significant step towards global cooperation in addressing the challenges posed by advanced AI systems. Our analysis reveals a landscape characterised by diverse approaches, varying resources, and shared challenges.

Despite political changes, the UK AISI is likely to remain the leader in the international AISI network, due to its early founding, significant funding, and effective implementation of key success factors. It has successfully attracted top talent, maintained operational speed through political support, and established a flexible structure with access to cutting-edge information on AI advances.

The US AISI, while facing funding uncertainties and potential political shifts, holds the potential to become a key player if it can secure long-term funding and bipartisan support. Its success could reshape the landscape of international AI governance. However, struggling to secure consistent or substantial funding and facing budgetary constraints alongside political pressure from a future president whose stance on AI safety is still unclear could lead to the US AISI playing a smaller role internationally, with the UK leading the charge.

The EU has the potential to have a large impact on international AI Governance being the regulatory first-mover. However, it will need to seriously adjust its approach in order to mitigate the EU AI Office’s weaknesses as an AISI.

Japan’s focus on international standards, Singapore’s balanced governance model and Canada’s secure funding suggest that they will all be able to contribute to the international AI Governance field.

As AI technology continues to advance at a rapid pace, the existing work being done by AISIs will only grow in importance. Their success will depend on their ability to attract and retain top talent, move quickly in response to new developments, and maintain the flexibility to adapt to an uncertain future. The AISI Network has the potential to play a crucial role in shaping the future of AI development and governance, ensuring that as AI systems become more powerful, they remain aligned with human values and interests.

The path forward will require continued cooperation, innovation, and commitment from all stakeholders – governments, industry, academia, and civil society. By learning from the successes and challenges of the current AISI landscape, we can work towards a future where AI safety is at the forefront of technological progress, enabling the benefits of AI while mitigating its risks.

Footnotes

1. Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy and South Korea also joined the network agreement but are not included in this analysis because they haven’t announced substantial detail on their plans.

2. Roles inspired by a forthcoming Institute for AI Policy and Strategy publication

3. Institutionalization, Leadership, and Regulative Policy Style: A France/ItalyComparison of Data Protection Authorities, (Righettini, 2011). Link.